Deep-C at Sea: Disciplines Converge to Improve Response to Gulf Contaminants

– August 14, 2012

After the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, people asked basic questions: what happened to the oil, what did it affect, and how did it change the Gulf of Mexico?

Getting answers is no simple task. It requires a greater depth of understanding than we now have about the processes operating within and the connectivity between the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico and the coast – critical components to obtain accurate answers and either forestall or prepare for future incidents.

Scientists are studying these processes and connections now to understand effects of the oil spill and improve response to other incidents that threaten the region’s valuable natural resources. Understanding these relational ties – the physical, chemical, and biological attributes of the northeastern Gulf of Mexico marine ecosystem – is what drives this collaborative research endeavor that transcends disciplines and institutions.

”As an ecologist, I am interested in unraveling that invisible fabric that binds species to one another and to the physical world in which they are found, bonds that are often revealed only in the face of disturbance . . .in this case, a major disturbance in the form of a massive oil spill.” Felicia C. Coleman, Deep-C Scientific Director.

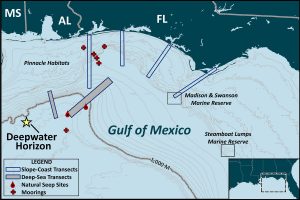

The Deep Sea to Coast Connectivity in the Eastern Gulf of Mexico (Deep-C) Consortium, funded by a Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) award, consists of ten institutions across six U.S. states and Norway. Headed by Dr. Eric Chassignet at Florida State University (FSU), this consortium is engaged in a rigorous three-year, field-intensive sampling effort focused on processes that influenced the fate and transport of the oil, gases, and dispersants and the consequences to living marine resources from the coast to the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Making connections among these processes is critical for developing better forecasts and risk assessments for future.

The Deep-C research tasks are integrated, with each providing a framework for the next, starting with a thorough description of the bathymetry and topographical features that define the seafloor’s physical characteristics. The Geomorphology Team uses a combination of bathymetric maps provided by NOAA’s RV Okleanos cruises, historical data, and videographic and acoustic surveys to identify key features of the sea floor that influence the movement of water and the distribution and abundance of marine organisms. In a series of cruises, researchers will map, characterize, and quantify the underlying geology and benthic habitats, including natural hydrocarbon seeps, hard ground, deep-sea coral communities, and essential fish habitats.

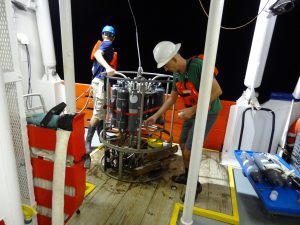

Knowing the hydrodynamics of the system – the seasonal currents and episodic oceanographic and atmospheric drivers – helps explain the transport of pollutants, sediments, and organisms, and the development of hypoxic areas. The Physical Oceanography Team uses instrumentation that includes a combination of moorings and subsurface floats deployed near the head and within the De Soto Canyon. A new float technology measures currents near the seafloor with “bottom drifters” as opposed to surface drifters, profiling the water column regularly for temperature, salinity, and oxygen, and other parameters.

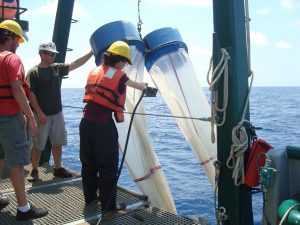

The next two tasks – geochemistry and ecology – are inextricably linked. The Geochemistry Team uses natural chemical tracers to determine the paths through which oil moved through the water column, penetrated bottom sediments, and reached marine animals. The Ecology Team focuses on understanding the biological diversity, distribution, and abundance of a wide range of organisms within the region: primary producers; sediment-dwelling microbes; benthic macrofaunal invertebrates; and dominant scavenger, prey, and top-level predatory fish that are both ecologically and economically important. These scientists analyze tissue samples for exposure to heavy metals and hydrocarbon derivatives.

The geochemical and ecological data from these analyses contribute to the development of a food web model that tracks the movement of these compounds through the ecosystem and addresses the ecological, economic, and management consequences of the oil spill and other types of large-scale anthropogenic disturbances affecting the northeastern Gulf of Mexico.

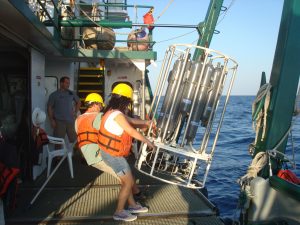

The Deep-C teams use specially-outfitted research vessels to conduct their field work: the Florida Institute of Oceanography’s RV Bellows and RV Weatherbird II and the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium’s RV Pelican.

The overarching goal of the research conducted by the Deep-C Consortium is to link the food web model with a regional three-dimensional earth system model. The Modeling Team incorporates quantitative data on earth-ocean-atmospheric coupling with the biogeochemical and food web dynamics of the northeastern Gulf of Mexico.

The combination of earth system and food web models will produce a powerful tool set that can be used to investigate and forecast environmental impact scenarios, and to assess the influence of hydrocarbon releases on fisheries, tourism, and human health. – Eric Chassignet

Deep-C scientists are committed to increasing the pipeline of future STEM professionals and to helping young scientists become productive and independent researchers. More than 50 undergraduate and graduate students and post-doctoral fellows are directly involved in Deep-C research.

Through several student programs, participants experience first-hand what it is like to develop meaningful scientific questions, design studies to address the questions, and execute the studies in the field.

High school teachers have opportunities to participate in hands-on and cutting edge science through educator programs. These educators also receive training to incorporate what they learn during the program into hands-on activities for students, one of which is to build and operate a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV), instrumentation that uses a camera to explore the sea floor.

These teachers and students share their experiences through the Deep-C Voices from the Field website. There, a graduate student shares her interactions with 3rd grade students at Pensacola Beach Elementary School and an undergraduate summer intern describes her participation on the microbiology sampling cruise. Scientists also share their research cruise experiences: read Dr. Snyder’s blog about the July 2012 ecology cruises and Dr. Locker’s blog about the July 2012 geomorphology/seafloor mapping cruise.

In support of research conducted in the Gulf of Mexico – including that of the Deep-C Consortium – the FSU Office of Research committed $1.6 million towards the construction of a new 65-ft research vessel tailored for many aspects of the work described here. The vessel arrives in late November, ready to support the research of all GOMRI consortia working in the Gulf of Mexico.

This research is made possible by a grant from BP/The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative. The GoMRI is a 10-year, $500 million independent research program established by an agreement between BP and the Gulf of Mexico Alliance to study the effects of the Deepwater Horizon incident and the potential associated impact of this and similar incidents on the environment and public health.

© Copyright 2010- 2017 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).