GoMRI Science Teams among First Responders to Galveston Bay Oil Spill

– April 22, 2014

On March 22, a cargo ship collided with a barge carrying approximately 4,000 barrels of bunker fuel oil in Galveston Bay, Texas. An estimated 168,000 gallons spilled into the Houston Ship Channel, prompting officials to shut it down for cleanup.

Within days scientists from two research consortia funded by the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) were on site alongside government and industry workers, collecting baseline information to assess impacts.

Science on the Scene

Chris Reddy, a senior marine chemist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI) and a member of the Deep Sea to Coast Connectivity in the Eastern Gulf of Mexico Consortium (Deep-C) has studied the weathering of different oils throughout his career. While much of his recent research has focused on the 2010 Deepwater Horizon incident, he maintains that every spill and seep should be studied because all offer new information. “My ears are always open for a new spill,” said Reddy. “It’s kind of like buying a house—location, location, location.” A surface spill in a bay behaves differently than one from the sea floor. Each provides an opportunity to learn and improve responses to future spills, including damage assessment and cleanup.

Reddy was in California when the Galveston Bay accident occurred, so Bob Nelson and Bob Swarthout, WHOI researchers in marine chemistry and geochemistry, used NOAA model predictions to track the oil and then sampled it. Swarthout reported that even though the volume was about the same as in a third of an Olympic-sized swimming pool, the oil was like “a large ‘raft’ that floated out of the Bay and was pushed by wind and currents over 200 miles to the south.” On March 27, this raft made landfall at Matagorda Island. Days later this duo collected oil that washed up on barrier islands farther to the south, including Mustang Island. They also discovered fresh oil on the Bolivar peninsula to the north of the spill site. They collected samples to use as references when the team returns to determine if oil from this spill continues to impact these beaches and describe how it changes over time.

“Our lab specializes in chemically ‘fingerprinting’ oil samples,” explained Swarthout. “Using a number of different methods, we can definitively tell if oil from a particular location came from a certain source” and track the manner in which it degrades.

Brad Gemmell, a marine biologist at the University of Texas Marine Science Institute (UTMSI) and a member of the Dispersion Research on Oil: Physics and Plankton Studies (DROPPS) team, echoed Reddy when discussing the differences in oil at Galveston Bay and from the Deepwater Horizon incident. “This oil didn’t lend itself to dispersant as it was thicker and mostly on the surface,” explained Gemmell. “The primary mode of collection was skimmers. We think this oil didn’t spend as much time in the water column.”

Scientists with the DROPPS consortium are interested in oil as it moves through the water column and the effects of different agents on its travel path. They also look at the weathering process, but their primary focus is effects on planktonic populations and how they in turn impact the oil. Gemmell summed up DROPPS’ focus by saying, “We’re looking at both sides of the coin.”

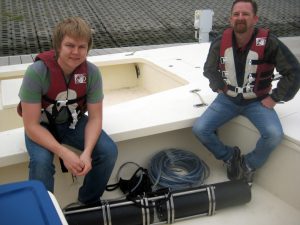

Gemmell and UTMSI marine biochemist Hernando Bacosa worked with students Larry Brock and James Lassmann from Texas Tech University (TTU) on a Texas A&M University at Galveston research vessel. They attended briefings with the U.S. Coast Guard and the Texas General Land Office on March 27, securing permission to collect samples within the closed area accompanied by a Coast Guard official.

Working Towards a Shared Goal

The port of Houston is home to the world’s second largest collection of petrochemical processing facilities. With this volume of oil-related traffic, the Houston Advanced Research Center estimates that 285 small spills occur in the Bay annually. Each oil specimen has a different chemical fingerprint depending on the source, and NOAA will provide an oil sample from this spill for researchers to use.

Both consortia teams found evidence of these multiple spills. Gemmell explained that this source oil is of the utmost importance for scientists to be certain their samples are from the same spill as “it can start changing even within a few hours.”

Because researchers want to gain information to help mitigate the spill’s negative impacts, members of both consortia say there is very little territorialism regarding data. For example, NOAA readily shared information about the anticipated travel path of the oil.

“It’s a really a good thing about academics in the oil spill community, that they’re so willing to share primary evidence so easily,” said Reddy. “It’s very comforting.”

The GoMRI Effect—Rapid Response

All of the researchers discussed how being a part of a larger, well-funded science community has enabled them to learn more in a shorter time period.

Swarthout was surprised at the security when he and Nelson arrived, noting, “access to most of the impacted beaches on the north end of Galveston Island was restricted by police roadblocks. We tried to find a way to get close to the spill site, but were consistently turned back.” NOAA and the Coast Guard eventually approved the two to enter, in part due to the positive relationships Deep-C researchers have developed while conducting GoMRI-funded work.

Gemmell also felt certain that he and his colleagues would not have been able to “cut through the red tape” of bureaucracy and get permission to sample in a timely manner without being a part of an organization like GoMRI. Additionally, the team used a specialized high-speed underwater three-dimensional holographic system to profile the water column, technology that has rapidly and vastly advanced with GoMRI funding.

“We were able to improve the prototype so that it was ready just in case something like this happened,” said Gemmell. “Also, being under the GoMRI umbrella lent a little more credibility to our cause. It allowed us to get into areas we might not have been allowed in otherwise.”

Reddy said that “trying to find scientific support before Deepwater Horizon was very challenging.” He added that with GoMRI in place, “we can afford to expand our horizons.”

Access during federally-regulated disasters such as oil spills or hurricanes have been a challenge for scientists interested in collecting timely information. This was a topic during the main plenary session at the January 2014 Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill and Ecosystem Sciences Conference. Former federal regulators and scientists contributed to this discussion and made suggestions to streamline future response.

The GoMRI Effect—the Best Young Minds

GoMRI is also making a difference by attracting young scientists to the field. Graduate students and postdoctoral researchers are actively involved in GoMRI-funded research, growing an experienced Gulf scientific community. For the Galveston Bay spill, both Deep-C and DROPPS called upon their ready and capable young researchers.

Gemmell and the TTU students working with him had never sampled an oil spill firsthand. They did so using the latest technology, the underwater holography system used in DROPPS research, to profile this oil and biological agents in the water column.

Swarthout, whose field of study was atmospheric chemistry before the Deep-C consortium lured him out of the sky and into the water, had been at WHOI six days when Reddy called him to action in the Gulf. He described his first view of clean-up workers in Tyvek suits as “looking like something out of a sci-fi movie.”

“In all my time as an environmental scientist, I had never seen anything like this,” said Swarthout. “Organic pollutants in the food chain rarely result in such a spectacular visual, and air pollution rarely leaves an enduring impact after the event has passed.” Though he was “amazed at how rapid and – at least cosmetically – effective the clean-up effort was in some places,” he expects to continue to find samples of this oil spill because of the “evidence of multiple older spills in the same areas that could have persisted for years.”

Reddy is pleased that new, young scientists are involved with different incidents such as the Deepwater Horizon and Galveston Bay spills. Reddy said that experiences like these will help “the next generation of scientists to be nimble, to be ready for anything.”

Both groups will continue to study the spill over time. Since oil has washed up on the shores of Port Aransas where UTMSI is located, Gemmell and Bacosa will not have to travel far to continue their work. Because of the distance between WHOI and the sample sites, Reddy has enlisted the help of a professor at Texas A&M Corpus Christi who is having one of his classes as well as teams of high school students participating in the Deep-C Gulf Oil Observers (GOO) project collect samples going forward.

All of the GoMRI consortia have the same overarching goal studying this and other incidents—better understanding of impacts and more effective response.

**********

This research was made possible in part by grants from BP/The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) to the Deepsea to Coast Connectivity in the Eastern Gulf of Mexico (Deep-C) consortium and Dispersion Research on Oil: Physics and Plankton Studies (DROPPS). The GoMRI is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit https://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

© Copyright 2010- 2017 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).