John Farrington Conferred as AGU Fellow

– September 1, 2015

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) community congratulates Dr. John W. Farrington on his selection as an American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fellow.

Not more than 0.1% of all AGU members in any given year receive this honor, and all elected Fellows receive a majority of votes after going through a peer selection and committee vetting process.

Reflecting on this designation, Farrington said, “I am very honored by my AGU colleagues in ocean sciences, geosciences, and space sciences for being elected a Fellow. Anything worthwhile in science that I have accomplished is the result of interactions in research with numerous co-workers, colleagues, students, and post doctorates with whom I have had the honor and privilege to collaborate or advise.”

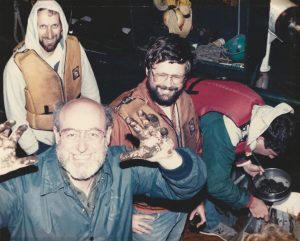

Farrington has held numerous leadership and education positions and received several prestigious honors during his 45+ year distinguished career. Some of these are featured in a recent profile of him by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s (WHOI) Oceanus Magazine.

Farrington shared a few of his career highlights and personal perspectives, harkening from his days as a graduate student and leading research at sea to upcoming family milestones.

His Mentors

Reflecting on his early years, Farrington spoke about Professor James Quinn, referring to him as one of the most dedicated graduate student advisors he had ever known:

I was Quinn’s first Ph.D. student and he was then an assistant professor, which meant that whatever we accomplished was important for his career. Nevertheless, he consistently pushed me and other students into the limelight of professional meetings and media interactions when there was interest in our research, always reminding us to speak from a strong basis of science.

Many other students under Quinn’s mentorship had successful careers, creating a long tradition and legacy as Farrington explained:

At meetings for oil pollution studies in particular, you are liable to run into several of Jim Quinn’s former students. For example at the annual Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill and Ecosystem conferences that GoMRI hosts, scientists such as Chris Reddy, Terry Wade, and Paul Boehm have been involved as well as their students, former students and former postdocs, and co-workers. A few of my former students, Liz Kujawinski and Bruce Brownawell, are now scientists involved with the Deepwater Horizon oil spill research. We stay connected and Jim Quinn has tongue-in-cheek names for us – the quinones and grandquinones.

Farrington considers his post-doctoral supervisor, the late Dr. Max Blumer, as arguably being the pioneer of modern oil pollution research in biogeochemistry. Blumer’s research on the 1969 West Falmouth oil spill and his involvement in the ensuing discussions helped Farrington understand the service aspect of science:

Blumer’s elegant analytical methods and informed interpretations in follow-on studies showed that when the slick disappeared, it didn’t mean the oil was gone. A huge debate followed with Max testifying before congress and at United Nations meetings. I asked Max if he felt his efforts were like banging his head against a wall, but he said, ‘Taxpayers have funded me for years and here’s an opportunity for me to give back information in an important area.’ Max’s comment had a very big impact on me in terms of understanding scientists’ responsibility to conduct fundamental research with applications for societal needs when the need presents itself.

Sea Challenges

Farrington was Chief Scientist of numerous research expeditions, yet some of his biggest challenges were maneuvering social customs and civil unrest that he and his team faced. One such situation was a cruise during Christmas and New Year’s 1975-1976. The expedition departed from and returned to Cape Town, South Africa. Farrington spoke of walking a fine line of being respectful of cultural and political situations even if you disagreed with them, as was the case when they were face-to-face with apartheid. There was a real threat of being arrested for actions that crossed lines of racial and gender segregation imposed by South Africans at that time, but his team carried on as Farrington explained:

Several women graduate students were on board. Since it was considered incorrect to have women in the port area, we secured special letters from the ship’s agent and traveled as a group. A woman reporter from an English-based South African newspaper came on board and interviewed one of the women graduate students. That interview resulted in an article about these women science pioneers, and I think that story had a positive influence there.

Logistical challenges that Farrington faced could have stymied their scientific efforts. In Cape Town, they were double-berthed and had to change ships. Everything on their research vessel had to be off loaded onto a barge, including the samples and equipment from previous cruise legs as the vessel was scheduled for a year-long expedition in the Indian Ocean. The barge went to a warehouse, the contents were reloaded onto another barge, and then stowed on a U.S. bound vessel. Costs were mounting. Farrington recalled having to sign for shipping expenses three times the amount allocated in their grants at that time for shipping.

The 1987 sediment sampling cruise on R/V Moana Wave from Guayaquil, Ecuador to Callao, Peru presented Farrington with safety challenges. He described situations where keeping the science going was sometimes the least of his troubles:

Guerrilla rebels blew up a power station not far from us just after we arrived in Callao, the port city of Lima. In the following days they gunned down a prominent government official, and we got out about a week before they blew up portions of our hotel. One scientist had a passport stolen during a national holiday and weekend period. We were fortunate that a colleague’s family friend was a U.S. embassy official and helped the scientist to secure a replacement passport.

Farrington recalled that in 1987 during debarking in Callao Peru, the Peruvian government had declared a two-day national holiday. Despite this, the science team had to have their substantial collection of frozen sediment cores and water samples somehow air freighted out before the ship departed on the next cruise leg. He explained how that played out:

The ship’s agent went to the port customs person’s home and to the airport customs person’s home, and we paid a large number of “non-baggage revision fees.” Then we crated and insulated the frozen mud and sent this one ton air freight shipment from Lima Peru to New York and then by truck to Woods Hole in 33 hours. The samples remained frozen and went into the WHOI lab freezers.

Farrington extended credit to the staff involved on those research expeditions and those working at WHOI, “One of the secrets that most people don’t understand is that there are large numbers of non-faculty professional people who really make the whole thing work with oceanographic research cruises.”

Science Collaboration and Legacy

Farrington is a fan of Louis Pasteur, who has been quoted as saying ‘there is no such thing as basic and applied research, there is only research.’ Farrington strongly believes that in order to make progress in meeting societal needs, there must be a vibrant, healthy, fundamental research base. He explained further:

Fundamental – or curiosity-driven research as I like to call it, borrowing the term from others – informs applied research dealing with societal needs and visa versa. That’s how I’ve done things in my career. Some colleagues have focused on basic research and others have focused on societal needs. Many have worked with the government, consultants, and companies. The key for progress is to honor each other’s contributions. If we do that, then everyone gains, especially society.

One of Farrington’s favorite quotes from Pasteur is that chance favors a prepared mind, and Farrington’s mentor helped him develop such a mind-set. He explained:

Quinn required that we read widely from various journals and bring back information to each other. I encourage scientists to go to seminars that are in other areas of research. Read Nature and Science. I love email notices about science discoveries. Get outside of science – I like history and philosophy. There are amazing things that open up our minds, such as interacting with artists who communicate science through the beauty of nature. It’s hard to be a renaissance person, but the more we try the better off we all are.

His involvement with interdisciplinary science has confirmed to Farrington that science collaboration leads to significant legacies. He explained how this applies to the GoMRI program:

There exists now at least two legacies for GoMRI – new knowledge being published and the interaction among graduate students, post doctorates, and senior scientists. We hope there is never another spill like the Deepwater Horizon, but odds are that a spill will happen again somewhere. But regardless of the event, the scientists and students affiliated with GoMRI have learned the importance of teamwork and connecting fundamental research to societal needs.

Family and Friends

Farrington tells students that as long as they can supply basic needs, they should pursue what is important to them. When asked if someone helped him pursue the science he loved even through lean times, he was quick to exclaim, “My wife Shirley!” He explained:

In the midst of my Ph.D. studies, we had two children because we wished to have children early in our marriage. Shirley worked as a Registered Nurse. Despite her paycheck and my fellowship stipend, we left the University of Rhode Island to continue my career as a postdoc at WHOI with only about $250 cash. Our daughter Karen, son Jeff, and family dog Lucy, and nearly everything we owned fit in our second-hand Ford galaxy station wagon. If my wife hadn’t shared my dream and been willing to work the 3-midnight shift several days a week and on weekends, I wouldn’t have been able to do what I’m doing. This May will be our 50th anniversary and we have much to celebrate, most importantly family and friends!

The GoMRI community joins in the accolades of Farrington’s exceptional contributions to science, his family’s support, and his service as a GoMRI Research Board member.

************

GoMRI is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit https://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

© Copyright 2010- 2017 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).