A Closer Look at Oil and Water

– May 8, 2013

Since the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, much has been written – in the popular press as well as scientific journals – regarding the potential impact the large volume of oil might have on the flora and fauna of the northern Gulf of Mexico.

But what about the oil’s impact on the water itself? In the months following the oil spill, researchers Wei-Jun Cai of the University of Delaware and Xinping Hu of Texas A & M University – Corpus Christi analyzed dissolved oxygen (DO) and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in the Gulf’s water column. In the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative funded study “Dynamics of Dissolved Inorganic Carbon and Dissolved Oxygen Following Natural or Manmade Petroleum Carbon Release into Marine Environments,” they will attempt to quantify their earlier observations and develop a protocol to measure this phenomenon in the future.

Just as they do on the earth’s surface, organisms in the water either produce or consume oxygen, depending on their species. Sea water has a set ratio of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and other nutrients that exists even in hypoxic areas, known as “dead zones.” After the oil spill, Cai and Hu noted a distinct change in the relationship between dissolved oxygen (DO) versus dissolved carbon dioxide (CO2) or inorganic carbon (DIC) generated during the period when large amounts of oil were decomposing in the environment:

If you plot the oxygen consumption and CO2 production together, if it’s marine-produced carbon, it always follows a similar pattern. When there is petroleum present, then data points are flying off the charts, with the same amount of oxygen consumption, you actually see less CO2 production. – Dr. Xinping Hu, Texas A & M University at Corpus Christi

Within the scientific community, there was some disagreement over what caused the change in numbers following the oil spill. Was the difference in the levels of DO and CO2 in the water chemistry caused by the extra oil in the environment or did oil simply coat the sensors (used to capture the oxygen data) and skew the numbers? Cai and Hu feel strongly that the data show a clear indicator of oil exposure and are extending their study in an attempt to prove definitively that these correlations differ in a healthy ocean versus one contaminated by oil.

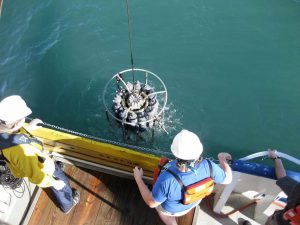

Long proponents of carbon cycle research in the Gulf of Mexico, Cai and Hu have collected water samples in the same region of the northern Gulf since 2006. In May, Hu will collect more water samples and will also collect sediment samples. At this point, according to their observations, the water column has likely returned to pre-spill conditions so they will look for potential lingering chemical changes evident in the sediment. Dr. Jianhong Xue from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute will work with Cai and Hu to analyze seven years of data for broader topics associated with the Gulf carbon cycle.

We’ve been working on the marine carbon cycle for so many years, and have been able to push forward carbon cycle issues in the Gulf of Mexico. The oil spill was large and very dramatic, but I also want to mention that there are a lot of natural oil seeps that release the petroleum carbonate all the time. We want to study how this carbon moves, but we don’t have a good way to quantify when these smaller leaks occur in the natural environment. It’s something we need to pay attention to. This could be a long term goal for the scientific community, to try to find out exactly how much carbon is being released into our oceans in the form of petroleum. – Dr. Xinping Hu, Texas A & M University at Corpus Christi

Ultimately, Cai and Hu plan to develop a product to help other scientists studying the carbon cycle in the world’s oceans: a standard protocol to evaluate the degradation of petroleum carbon and associated oxygen dynamics. The data collected in the Gulf will go towards the creation of an algorithm for detecting oil degradation signal. Hu feels that with the justified concern regarding the presence of greenhouse gases in the environment – the main product of fossil carbon usage – that any additional data on the carbon cycle, in the air or under water, can help scientists broaden their understanding of those issues and how they are related to climate change.

This research is made possible by a grant from BP/The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative. The GoMRI is a 10-year, $500 million independent research program established by an agreement between BP and the Gulf of Mexico Alliance to study the effects of the Deepwater Horizon incident and the potential associated impact of this and similar incidents on the environment and public health.

© Copyright 2010- 2017 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).