Students Are Field Tested During Emergency Response To Hercules Blowout

– November 18, 2013

|

Meet the Students Joy Battles conducts research for the ECOGIG (Ecosystem Impacts of Oil & Gas Inputs to the Gulf) consortium and is a member of the Joye Research Group at the University of Georgia. There, she is pursuing a M.S in Marine Sciences where she also received a B.S. in Microbiology and Psychology. Nathan Laxague conducts research for the CARTHE (Consortium for Advanced Research on Transport of Hydrocarbons in the Environment). He is pursuing a Ph.D. in Applied Marine Physics at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science and received a B.S. in Physics at University of Miami. Conor Smith conducts research for the CARTHE (Consortium for Advanced Research on Transport of Hydrocarbons in the Environment). He is pursuing a Ph.D. in the Applied Marine Physics Department at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science and received a degree in Physics with a concentration in Meteorology from the College of Charleston. Tiffany Warner conducts research for the CWC (Coastal Waters Consortium). She is pursuing a M.S. in Oceanography and Coastal Sciences at Louisiana State University and the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium and received a B.S. in Earth and Environmental Science at University of New Orleans. Sarah Weber conducts research for the ECOGIG (Ecosystem Impacts of Oil & Gas Inputs to the Gulf) consortium and is a Research Technician with the Montoya research group at the Georgia Institute of Technology. She will begin her Master’s in Biology in the spring. |

“Nothing like real world application to illustrate what a book cannot demonstrate.”—Tiffany Warner, Louisiana State University and CWC

In the early morning hours on Monday July 23rd the Hercules 252 rig blew out, spewing a mixture of gas, condensate, and possibly other hydrocarbons into the water and air. In four days, senior scientists – members of five Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) consortia – assembled a team and plan, obtained the RV Acadiana, prepped and shipped equipment, traveled to Cocodrie, LA, sailed to the blowout site, and began their work to assess potential impacts.

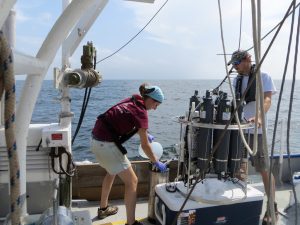

Five students – Joy Battles (ECOGIG), Nathan Laxague (CARTHE), Conor Smith (CARTHE), Tiffany Warner (CWC), and Sarah Weber (ECOGIG) – suddenly found themselves at the heart of this important mission, and not as sideline players. Their educational and research background and their personal fortitude were put to the test, working as a full-fledged response team to plan and execute this “herculean” data-gathering operation.

The coordinator of this response effort was University of Georgia biogeochemist and microbial ecologist Dr. Samantha Joye, science lead for the Ecosystem Impacts of Oil & Gas Inputs to the Gulf (ECOGIG) consortium. She said that at-sea experience, learning how to plan and stage cruises, is a requirement for oceanography students. However, this was no ordinary field work. “Planning and executing a rapid response cruise is a different animal as time is of the essence and there is no margin for error,” Joye explained, adding, “They were all faced with an incredible challenge yet they achieved remarkable success. I could not be more proud of them.”

Fast, Challenging Work

“The most important part of this endeavor is the precedent it sets: for marine scientists to respond quickly to a disaster in order to study it. It adds an immediately practical dimension to the work.” – Nathan Laxague, University of Miami and CARTHE

Laxague and Smith led the drifter deployment from start to finish. After helping develop a plan before leaving Miami, they prepared the surface drifters, attaching GPS units and long-life batteries. Together they drove from Miami to Louisiana, sailed to the blowout site, and launched the drifters. All of this happened very quickly, as Smith noted, “an emergency deployment of the drifters was planned and executed in less than three days.”

Battles and Weber together served as co-chief scientists for a portion of the cruise, guiding the water column and sediment sampling around the blowout site as well as collecting samples for later analyses of methane levels and biological activity related to carbon and nitrogen cycling. Weber explained, “We had to coordinate and execute a strategic sampling plan given the evolving circumstances of the blowout and the capabilities of our scientific gear and personnel.” Though Weber had done similar work, she said, “previous to this cruise…the responsibility had never fallen on my shoulders.”

Warner provided critical logistic support as groups hurriedly arrived and scrambled to load the research vessel. Once at sea, she collected water column samples at multiple locations and various depths to measure respiration rates. The blowout had the potential to cause depletion of oxygen in the marine environment. Warner explained that getting to the site quickly “allowed us to collect time sensitive data to characterize the incident site.”

Meaningful Mission

“The previous sleepless, hectic three days had distracted me from the reality of why we were doing all this work. As the crippled and damaged Hercules rig came into view, I truly realized the importance of our mission and the efforts felt worthwhile.” – Conor Smith, University of Miami and CARTHE

Smith went on to explain the potential significance of this work, “Had there been a contaminant of some sort released, our drifters would have provided one-of-a-kind data to predict the transport of it in the ocean.”

Battles commented on the cohesiveness with which all the parties involved worked, which meant that “much more was accomplished than any individual could have been achieved working alone.”

Warner agreed it was a wonder seeing “scientists from different parts of the nation and in very different disciplines effectively communicate to tackle a research project.” The larger importance of their work struck her when she realized, “Every decision I made would impact the scientific findings of not only my lab, but ultimately would be integrated into the larger picture.”

Hand-in-Glove Fit with Graduate Studies

“This specific research experience has directly contributed to my decision to pursue a postgraduate degree in biogeochemsitry and has given me an exciting taste of what it’s like to lead an oceanographic expedition.” – Sarah Weber, Georgia Institute of Technology and ECOGIG

During the mission, these students actively and significantly contributed to their respective consortium’s projects – and this experience in turn contributed to their own academic goals. Laxague said, “My degree involves the planning and fulfillment of fieldwork, frequently with time constraints. Our work at the Hercules site was right in line with that.” Battles, studying microbial community composition, said that “the sampling goals of this cruise were closely related to my research.”

For Warner, this experience connected classroom learning to real-world application: “It is one thing to read [about core oceanography disciplines] in a book or hear it in lecture, but to be in the field and utilize the methods you’ve spent countless hours learning, helps you to integrate all the parts you’ve been taught and how you can actually apply it.”

Messages for the Public

“As long as humans endeavor to extract oil and gas resources from the Gulf’s seabed, it is important for scientists to study the consequences of such accidental releases.” – Joy Battles, University of Georgia and ECOGIG

Battles continued speaking about the impact on the Gulf’s fragile ecosystems, “It’s easy to overlook the effects of a natural gas leak because gas is invisible to the eye, but methane is an important contributor to global warming and it plays an important role in oceanic food webs.”

Weber explained that this research is critical because oil and gas fill a large and necessary portion of our energy needs: “It is our responsibility to understand the impact of oil/gas spills on the environment to know how to better respond and more effectively mitigate the effects.”

As unfortunate as this event was, it provided an opportunity for researchers to test their “rapid response” plans in a real, serious situation and learn more about the ocean and its reaction to potential pollutants. It also provided an amazing experience for these five students, and their work will inform future response efforts. As Laxague explained, “This is an exciting time in the fields of marine science – for the good of society and world we live in at large.”

Read more about the immediate response: Scientific Dream Team Conducts Rapid Response Research at Hercules Gas Blowout.

This research was made possible in part by Grants from BP/The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) to CARTHE, C-IMAGE, CWC, ECOGIG, and GISR. The GoMRI is a 10-year, $500 million independent research program established by an agreement between BP and the Gulf of Mexico Alliance to study the effects of the Deepwater Horizon incident and the potential associated impact of this and similar incidents on the environment and public health.

© Copyright 2010- 2017 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).